By McKenna Asakawa

If a pole barn with an open floor plan could have secluded corners, Scott Atkins would be working from one of them. I know this because that’s exactly what Scott created for himself: when I first interned at our airy HQ in 2015, Scott’s desk was the only one sheltered by a propped-up portion of prefabbed treehouse wall.

Scott’s makeshift private office was eventually framed in and paneled with beetle-kill pine. It is from this blue-stained wood fortress that Scott transforms many of Pete’s drawings into engineered, permitted, and buildable treehouses.

On the daily, Seattle Public Radio emanates from Scott’s lair, a (singular) giveaway that he is in the building. It also conveys his passion for music (he’s a drummer in a band) and signals that his sheltered quarters are not meant to inhibit interaction or connection with coworkers. Quite the opposite: the people initially drew Scott to the job.

“The collaboration here is something I’d never experienced,” Scott says solemnly. “When I first met them, the people here exhibited an overlap of knowledge, experience, creativity, and competency. I could tell they were top-quality, the kind of people I’d want to have long-term relationships with.”

Scott has a penchant for founding long-term relationships with the people he works with: his previous boss gave a speech at Scott’s wedding, and his former business partner is his childhood best friend. Another lifelong relationship of Scott’s? His connection to the construction industry. As the son of an engineer, Scott grew up around building. Scott’s first adult job was in the concrete industry, which he then worked in for 15 years.

“Concrete is an unforgiving job,” Scott attests. “I threw out my back doing it when I was only 21. I like to compare it to people who run marathons: there’s this weirdly satisfying body high in doing it, the race to finish while balancing a ton of variables. It doesn’t take a lot of thinking: it’s all feeling, like sculpting. The part I miss is the banter with the other workers.”

Scott cut his project management chops by running his own concrete business. After ten years of managing his own jobs, Scott was hungry for a career change and began working for a framer and homebuilder.

Around 2013, Robyn, Scott’s wife, connected him with Pete—in a stroke of small-town serendipity, Robyn had been Henry and Charlie Nelson’s preschool teacher and a part-time nanny for all three Nelson kids. Scott met with Pete and Emily at TreeHouse Point and started working as a carpenter in the prefab shop shortly thereafter. Six months later, Scott moved into the project management role.

Scott Atkins and his family

Scott Atkins and his family

When Scott speaks, I get the sense that he is deliberate about his words: that he says what he means and means what he says. I ask him to describe his work as a project manager.

“This is an unusually fast-paced job.” Scott gives a characteristically thoughtful pause.

“Treehouses are small, so the jobs turn over much more rapidly than traditional homebuilding. And the projects are incredibly diverse: always new, always different. As a project manager, my job is to collect all the pieces and set the table, then hand it off to people in the field. You do all the planning and prep work prior to the first day of construction and then fulfill a support role after that.”

Do you like the pace?

“The pace appeals until it doesn’t. It keeps things fresh but can be challenging. Another challenge is sourcing subcontractors to help in all the different parts of the country we work in. If you just work locally, you have a team of subs you know you can trust. In this job, we have to find and trust new subs every three weeks.”

How do you find trustworthy people?

“I can tell within 30 seconds of talking if someone is interested and a good fit. It’s like a ‘Spidey’ sense. I always take personality first over qualifications—I’m more interested if we can have a successful working relationship.”

Scott feeds off the challenges of the job, be they logistical, mathematical, or bureaucratic. “I’ve always been kind of a glutton for punishment,” Scott says with a shrug. “Always willing to take on a lot in work and in life— I’ve never really turned down a challenge.”

Scott understands that challenging environments often foster the greatest innovations. Whether in concrete or homebuilding or treehouse design, Scott has sought to work with companies at the forefront of their industries for their commitment to creative solutions. “I like to be in an environment of invention,” Scott muses. “The creativity at Nelson Treehouse was appealing. I guess I’m kind of an engineer at heart.”

Indeed, one of Scott’s favorite parts of the job is engineering in a broad sense, or as he titles it, “The fine details: the components that need to be invented and the unique systems that need to be created.”

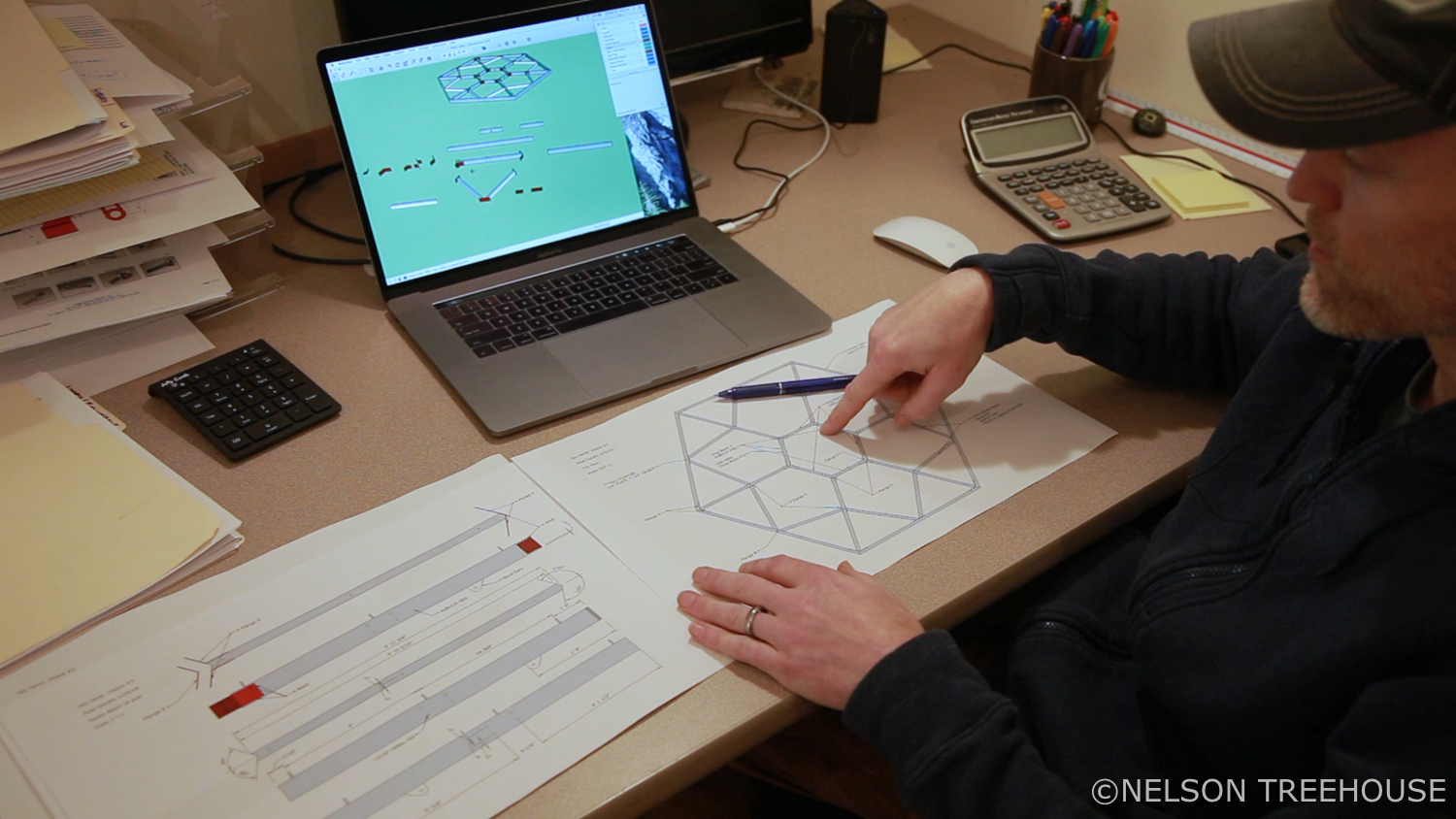

A recent project of Scott’s that required inventive engineering was the lotus-shaped steel substructure for Bilbioteque at Treehouse Utopia. The substructure consists of 36 distinct pieces, which coalesce around a single cypress to form an ultra-strong foundation for the 400-square-foot treehouse.

Scott works on the steel substructure to biblioteque at treehouse Utopia

Scott works on the steel substructure to biblioteque at treehouse Utopia

Scott’s interest in the fine details also transfers to his work in understanding how building code applies to treehouses. Scott is our resident permitting specialist, having secured over 20 permits for treehouses in 11 states and 14 jurisdictions.

How did you go about understanding the way that building code applies to treehouses?

“In regular construction, you just have to understand the code’s basics, as the requirements are straightforward. But with treehouses being so unique, I had to sit down and read code and really understand its intent. I’ve probably read over 1,600 pages of code and honestly, I find it really intriguing.”

What is it about building code that interests you?

”The building code provides for innovation—its spirit and intent is to ensure safety and longevity, not to inhibit creativity. I’ve never felt that the permitting process for treehouses is complex or scary.”

Many DIY-builders do see permitting as daunting, though. What advice would you give them?

“They really don’t have to feel intimidated. It’s pretty cut-and-dry: the building department will ask you questions, and you will provide answers. Obtaining a permit for a treehouse is mostly like regular houses, although some elements of treehouses are unique and therefore sometimes not always prescriptive by code.”

In 2015, Scott spearheaded our project to test the load-bearing capacity of our treehouse attachment bolts (TABs) at Washington State University (WSU). This test came at the request of a building department: load capacity figures were required to meet code standards for alternative hardware. Scott relished the collaboration with WSU engineers and the findings from the tests.

“I was all into it: the strong machines breaking things, the lab coats and safety glasses. It was awesome,” Scott recalls warmly, with a laugh. “I like being a part of science, running tests that contribute to the treehouse community—builders were saying it was so helpful to get those results. And of course the validation of the strength of our hardware was incredible.”

scott Atkins tests the load capacity of TABs at Washington State University

scott Atkins tests the load capacity of TABs at Washington State University

(You can read about the results from our TAB testing, here. And check out our video on the experience, below.)

Recent treehouse projects that Scott has managed include the Semper Fi Treehouse in Pennsylvania, Hot Tub Rumpus Room in Washington State, and three of the treehouses at Treehouse Utopia (Biblioteque, Carousel, and Chapelle). I ask him which Nelson treehouses have been his all-time favorites.

“It tends to always be the one I’m currently working on, as it’s new and takes my imagination,” Scott replies. “The Space Crab treehouse stands out, though. It was so weird and different, with all that zinc and metal.”

Some people say the Space Crab isn’t truly a treehouse, since it’s supported by posts.

“I don’t subscribe to the idea that using posts does not make a treehouse. A treehouse is an experience. If you need a post to create the experience of being in the trees, then use it. The post should be celebrated.”

the Space crab treehouse

the Space crab treehouse

If you could build your own dream treehouse, what would it look like?

“It would be a motorcycle shop. One room—not too big—with a work bench, tools, and space for my bike. And it would be all wood. Definitely no concrete.”

Carousel and Chapelle at Treehouse Utopia were two of Scott Atkins’ recent projects

Carousel and Chapelle at Treehouse Utopia were two of Scott Atkins’ recent projects

When he’s not working on treehouses, or tuning up his motorcycle, or backpacking around the Pacific Northwest, Scott plays drums with his rock and roll band, Halftrack. (You can listen to Halftrack as the soundtrack to many of our videos, including this behind-the-build video on Treehouse Utopia.)

What do you enjoy about playing music?

“The headspace. It’s similar to working on my bike, but more collaborative. Some people say you need to tune out [to find headspace], but I’d actually call it tuning in. Music isn’t created, it’s channeled. You tune into some open channel, and it’s weird and so cool when four people can tune into that same channel.”

Scott Atkins on drums with his band, Halftrack

Scott Atkins on drums with his band, Halftrack

With his many talents and passion projects, I wonder aloud what activities Scott has yet to try.

“I want to fly.” Scott laughs.

“By paramotoring, that is. Did you know there are paramotoring schools that will train you to fly distances? Check it out on YouTube. I like that it involves a motor—I like the noise. Silence isn’t really for me.”

Scott Atkins on his Motorcycle

Scott Atkins on his Motorcycle

Scott atkins with his wife, Robyn, and son, Cedar, on a camping trip at Mt. Rainier National Park

Scott atkins with his wife, Robyn, and son, Cedar, on a camping trip at Mt. Rainier National Park

At the close of our interview, I ask Scott to share one piece of advice he would give his 20-year-old self. For this question, Scott doesn’t skip a beat.

“‘It never hurts to ask.’ That’s grandma wisdom. I’ve experienced some amazing and weird things just by asking. From getting to use a Ferrari for a weekend job to touring a historic building in Seattle late one night… I’ve learned a lot about the world and other people that way.”

You can read all our Staff Spotlights on our intrepid crew here.